Oppenheimer's Jewish Angle

Looking into the real history and the justifications depicted in Christopher Nolan's Oppenheimer, I will attempt to analyze the real and fictionally depicted Jewish angle of J. Robert Oppenheimer.

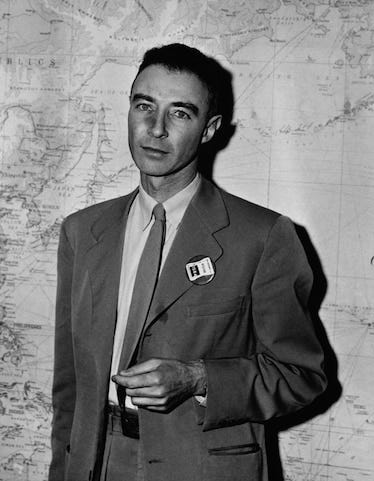

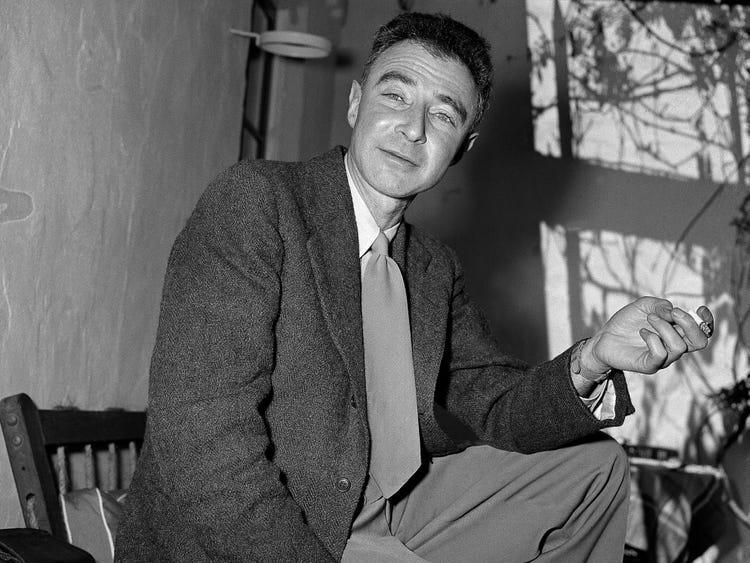

Julius (J.) Robert Oppenheimer was born April 22nd, 1904 to German-Jewish immigrant parents in New York, NY. He was raised in a secular upbringing surrounded by wealth and rounded education, providing him with the opportunities that led him to his academic and scholarly brilliance as a theoretical physicist and the spearhead of the creation of the atomic bomb used in World War II against Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Although his parents were first and second-generation German immigrants, Oppenheimer always insisted that he didn’t speak German. He also maintained that the “J” in his full name stood for nothing at all despite the Julius present on his birth certificate, indicating his father had passed on the Jewish name. Which Nolan’s Oppenheimer also confirms in the film.

Despite his flimsy connection with Judaism, Oppenheimer’s life was not exempt from antisemitism. Academic brilliance alone could not shield him from it. He entered Harvard in 1922 just as the university moved toward a quota system over the number of Jewish students allowed admittance. Nonetheless, he kept to his studies and stayed away from the campus controversy. He tried to befriend non-Jewish students throughout his time in the university, but the prevailing antisemitism doomed those efforts and left him with a predominantly Jewish friend group. After earning a bachelor’s degree in Chemistry from Harvard in 1925, he conducted research at the University of Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory and completed his PhD at Göttingen University, in pre-Nazi Germany, under Max Born, a pioneer of quantum mechanics. Before he got to Cambridge, though, a Harvard professor wrote him a recommendation letter that captured the institutionalized antisemitism present in academia: “Oppenheimer is a Jew, but entirely without the usual qualifications.”

Oppenheimer returned from his stay in Europe to teach physics at the California Institute of Technology and the University of California, Berkeley. While at Berkeley, he tried to secure a position for his colleague Robert Serber and was rebuffed by his department head Raymond Birge, who said, “One Jew in the department is enough.” He did not push back on the decision, later hiring Serber to work along side him on the Manhattan Project.

Throughout Oppenheimer’s life, he stayed away from current events. Oppenheimer once said, “I never read a newspaper or a current magazine like Time or Harper’s; I had no radio, no telephone; I learned of the stock market crash in the fall of 1929 only long after the event; the first time I ever voted was in the presidential election of 1936.” This all changed in the mid-1930s with the rise of Hitler and Nazism in Germany. “I had a continuing, smoldering fury about the treatment of Jews in Germany,” Oppenheimer said in his testimony. “I had relatives there, and was later to help in extricating them and bringing them to this country. I saw what the [economic] Depression was doing to my students… And through them, l began to understand how deeply political and economic events could affect men’s lives.” In addition to rescuing family members, while teaching at Berkeley, he earmarked 3% of his salary to help Jewish scientists escape Nazi Germany. By World War II, his drive to defeat Nazism in Germany would propel him to direct the Manhattan Project at the Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico.

Top scientists in Los Alamos, whom were also mainly Jewish and immigrants, were affected deeply by the Holocaust, many losing relatives abroad. In Jennet Conant’s book 109 East Palace: Robert Oppenheimer and the Secret City of Los Alamos, she writes “[The scientists] had all been told, had absolutely believed, the atomic bomb would be needed to bring the Nazis to their knees. But that had happened without them.” Emilio Segrè, a lead scientist on the Manhattan Project, stated “Hitler was the personification of evil and the primary justification for the atomic bomb work.”

In Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, Oppenheimer says “I know what it means for the Nazis to have a bomb.” Ernest Lawrence responds with, “And I don’t?” To which Oppenheimer says, “It’s not your people they’re hurting in the camps.” Immediately afterwards he is appointed to the Manhattan Project, providing a clear justification for Oppenheimer’s reasoning in joining the effort to create an atomic bomb to possibly use against Nazi Germany. The usage of “your people” by Oppenheimer in this line in reference to him being a part of the Jewish people is interesting considering his ambivalence to Judaism throughout his life. Isidor Rabi, a Polish Jew and close friend and consultant on the Manhattan Project, stated about Oppenheimer’s Judaism, “Oppenheimer was Jewish but he wished he weren’t, and tried to pretend he wasn’t.” This was a direct result of his secular upbringing and antisemitism faced in his life. A common defense mechanism used to protect yourself against prejudice is to hide your identity, which Oppenheimer did. Lewis Strauss, a Reform Jew who went against Oppenheimer and defaced his reputation in the 1954 trials, was jealous of his scientific notoriety and his rejection of Judaism. “Strauss also had to navigate being Jewish in an American society that didn’t totally embrace Jews, and it was somewhat of a threat to him to have somebody like Oppenheimer whose approach to dealing with his Judaism was to hide it.” In the film, Strauss is portrayed as having secretly orchestrated Oppenheimer’s downfall at the hands of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), in part by collaborating with Hungarian-Jewish physicist Edward Teller, who agreed with Strauss on the necessity of the hydrogen bomb.

This Jewish angle historically and creatively helps shape the story of Oppenheimer as a person and his reasonings for joining the Manhattan Project, as well as his early life and his life following the bomb’s creation. Telling the story of Oppenheimer without Judaism wouldn’t be right and Nolan does an excellent portrayal of Oppenheimer refusing to turn his back on the Jewish community, despite his little connection to it. Hence, the Jewish angle of Oppenheimer was a necessary one to accurately tell the story of the Manhattan Project, those involved, and the man directing it.